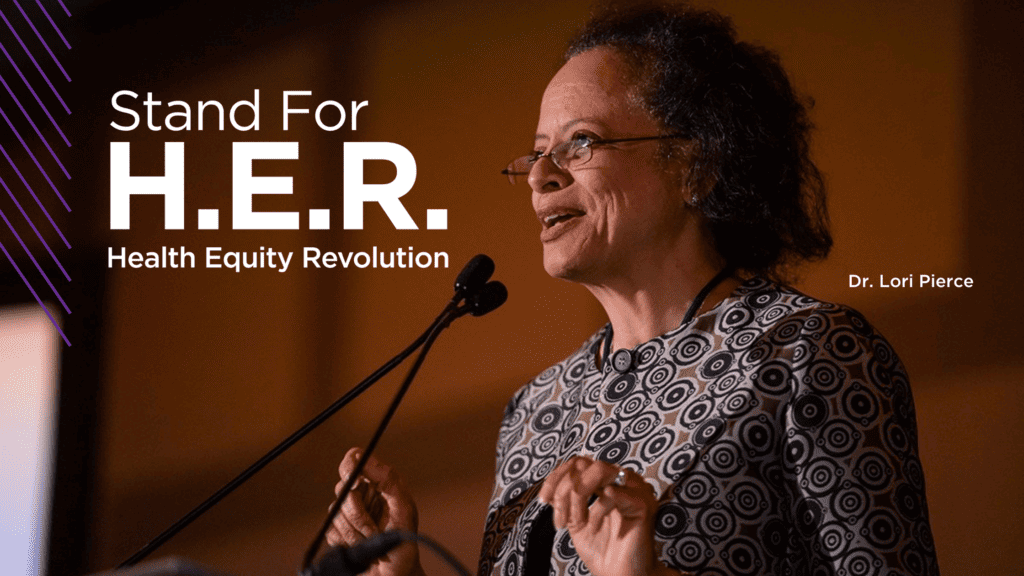

Radiation oncologist is dedicated to achieving equity in breast cancer care

Lori Pierce, a University of Michigan radiation oncologist and former Komen Scholar, is committed to improving outcomes for Black women with breast cancer.

She was the first Black woman president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the world’s largest organization of cancer doctors. Her one-year term ended in 2021, but equity continues to guide her work as chairperson of ASCO’s board of directors, among her other roles.

Biological factors partly explain why Black women in the U.S. are more likely to be diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer and have about a 40 percent higher death rate than white women. But Pierce says social determinants of health, which include having a well-paid job and living in a safe neighborhood with access to nutritious foods, likely play an even bigger role in influencing breast cancer outcomes for Black women.

“We have all these amazing therapies for breast cancer,” Pierce says. “But if we don’t ask the right questions – whether our patient has transportation to get it, whether she can get off work, whether she has caregiving issues – then all these therapies go for naught. We need to have a better understanding of the barriers that patients are facing so we can help address them.”

Her commitment to equity extends to quality of care.

Some studies have found that Black women often don’t get the best possible treatment, in part because they do not always receive the highest quality care at the facilities where they receive treatment.

A research collaborative Pierce directs is exploring ways to improve the delivery of radiation therapy. The collaborative is part of a statewide radiation oncology consortium.

“We’ve done research projects within the consortium to show that we’ve been able to improve the level of care of how radiation is delivered across the state,” she says, “and that’s impacted all women with cancer, including those with breast cancer.”

The research has helped lower-performing centers elevate their quality of care to the level of higher-performing centers for specific metrics.

“It’s incumbent on all of us to make it clear what the expectations are and where the bar should be set for all patients,” she says.

Increasing the number of Blacks and Latinos in clinical trials also will help to improve the quality of treatments and care for all breast cancer patients.

Pierce co-leads an initiative aimed at making sure that the number of people in clinical trials from historically underrepresented groups matches the racial diversity of the cancer population. The initiative is a collaboration of ASCO and the Association of Community Cancer Centers.

A recent study reported that the percentage of white and Black people willing to join clinical trials is about the same. Yet participation rates don’t reflect that reality.

“There are trust issues, but that fact clouds perceptions about Black people’s willingness to join clinical trials,” she says. “We have a low percentage of people of color in clinical trials because we don’t ask. We have to figure out how we are missing opportunities to involve patients.”

The initiative is developing a self-assessment tool to help research sites evaluate why and where in the process patients drop off, and a training tool is being created to help health professionals face and overcome their own implicit biases.

That work comes at a time when medical advances are giving Black women more treatment options.

“We’re learning that in many cases, ‘less is more’,” says Pierce. “The more we know about the biology of the disease, the more we can offer therapies that are not as intensive yet have as good an outcome.”

Surgical examples include sentinel node removal and breast conservation.

Examples of new advancements in radiation therapy include treating a portion instead of the whole breast and giving larger doses once a day over a shorter period of time than conventional radiation courses. Some patients may be able to safely skip radiation altogether.

Pierce’s research focuses on the biology of breast cancer, including studying drugs called radiation sensitizers that kill off more cancer cells when paired with radiation than radiation alone.

“‘Less is more’ is where we’re going for the future,” Pierce says. “Finding molecular markers will reliably determine which tumors need intensified treatment. And conversely, those molecular markers will tell us when we can back off.”

Employing a more diverse and culturally competent health care workforce also improves care.

“Not every Black patient needs a Black provider on her team, because we all need to be more culturally competent,” Pierce says, “but when you have a more diverse workforce, you bring in more diverse ideas that enrich patient care.”